Zahid Shahab Ahmed, Silada Rojratanakiat, and Soravis Taekasem, “The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in Social Media: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Tweets from Pakistan,” USC Center on Public Diplomacy, CPD Perspectives, October 2019. Ahmed (Deakin University, Australia), Rojratanakiat and Taekasem (University of Southern California) use critical discourse analysis to investigate how the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) was framed in social media (primarily Twitter) during the first six months of 2015. They conclude that most top Twitter handles originated in Pakistan’s government ministries. They promoted not just the CPEC but also China’s positive intentions toward Pakistan. These accounts also used Twitter to counter Indian critiques of CPEC. Negative tweets originated in India and opposition parties in Pakistan. Neutral tweets originated from news media in Pakistan and India. Overall, nearly half of the tweets in their data set were positive on CPEC.

Franklin Foer, “Victor Orban’s War on Intellect,” The Atlantic, June 2019, 66-72. Atlantic staff writer Foer describes the successful campaign waged by Hungary’s populist Prime Minister Viktor Orban against Central European University (CEU). Founded by financier George Soros and accredited in both Hungary and the US, CEU has at last succumbed to Orban’s relentless attacks on its legal status and academic freedom. Soros and CEU’s rector Michael Ignatieff are moving CEU to Vienna. Foer tells a complicated story. The Orban government’s tactics against Soros and the university. Soros and Ignatieff’s unsuccessful efforts to work out a solution. State Department Assistant Secretary A. Wess Mitchell’s request that CEU be allowed to stay. The Trump administration’s cuts in US assistance to free media in Hungary. Trump’s political Ambassador to Hungary David Cornstein’s handwringing over CEU’s fate coupled with his firm unwillingness to let CEU’s departure affect US relations with Orban. The Embassy PAO’s distress at the Ambassador’s lack of sensitivity to CEU’s plight. And concerns about the implications for CEU of Austria’s right wing turn.

Glenn S. Gerstell, “I Work for N.S.A. We Cannot Afford to Lose the Digital Revolution,” The New York Times, September 10, 2019. The National Security Agency’s General Council warns of four technological threats with profound near term implications for government agencies. First, “the unprecedented scale and pace of technological change will outstrip our ability to effectively adapt to it.” Second, we face “ceaseless and pervasive cyberinsecurity and cyber conflict against nation-states, businesses and individuals.” Third, an extraordinary flood of economic and political data about human and machine activity will transform the relationship between government and the private sector. Fourth, the digital revolution has potential to do pernicious harm to the legitimacy and stability of governmental and societal structures. Gerstell examines the combined effects of these trends, which he calls a “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” (Courtesy of Barry Fulton)

Natalia Grincheva and Robert Kelley, “Special Issue: Non-Western Non-State Diplomacy,” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, Volume 14, Issue 3, June 2019. In this important compilation, Grincheva (The University of Melbourne), Kelley (American University), and their co-authors move forward imaginatively on two under-researched trajectories in diplomacy studies. First, they provide conceptual and empirical support for understanding diplomacy as an autonomous activity engaged in by NGOs, civil society activists, firms, terrorist groups, and other non-sovereign actors in addition to states. Second, in what they identify as a “post-globalist” approach to diplomacy, their evidence is drawn from non-Western countries. Their work seeks to recalibrate a research agenda that has favored Western diplomatic practices. The articles in this HJD special issue are a rich repository of conceptual definitions, analytical assessments, empirical evidence, bibliographic references, and provocative claims by scholars at the cutting edge of diplomacy scholarship.

— Natalia Grincheva and Robert Kelley, “Introduction: Non-state Diplomacy from Non-Western Perspectives,” 199-208. See annotation above. The full text is available online.

— Iver B. Neumann (Oslo University), “Combating Euro-Centrism in Diplomatic Studies,” 209-215. “In a rapidly globalizing world, Euro-centrism . . . is both politically unjust and scientifically unsatisfactory, since it means knowledge production proceeds according to habit rather than need.”

— R.S. Zaharna (American University), “Western Assumptions in Non-Western Public Diplomacies: Individualism and Estrangement,” 216-223. Zaharna looks at how “unexamined assumptions may still restrict how we think and talk about public diplomacy as a global phenomenon.” She takes a critical look at two: “the first, ‘individualism,’ comes from the US context; the second, ‘estrangement,’ originates in Western traditional diplomacy.”

— Natalia Grincheva, “Beyond State Versus Non-state Dichotomy: The State Hermitage Museum as a Russian Diplomacy ‘Hybrid,’” 225-249. Grencheva argues that museums such as the Hermitage Museum and global network of Hermitage Foundations are a case of “hybrid” or “track one and a half” diplomacy that combine efforts of state and non-state actors. Hermitage Foundations strengthen “Russia’s role in international culture” and facilitate “constructive dialogue with foreign partners.”

— Anna Popkova (Western Michigan University), “Non-state Diplomacy Challenges to Authoritarian States: The Open Russia Movement,” 250-271. Popkova “uses a case study of the Open Russia movement to explore the public diplomacy potential of transnational NSAs [non-state actors] that represent domestic political opposition in non-Western authoritarian states.”

— Nur Uysal (DePaul University), “The Rise of Diasporas as Adversarial Non-state Actors in Public Diplomacy: The Turkish Case,” 272-292. Uysal looks at diaspora public diplomacy in a case study of how an adversarial diaspora “has transformed into a non-state actor challenging the Turkish state’s legitimacy.” She uses a “four-quadrant model” to examine relational dynamics between state and diaspora publics and Robert Entman’s cascading model to analyze media frames.

— Li Li, Xufei Chen (China Foreign Affairs University), and Elizabeth C. Hanson (University of Connecticut),“Private Think Tanks and Public-Private Partnerships in Chinese Public Diplomacy,” 293-318. Taking a “relational approach to public diplomacy,” the authors examine how private think tanks act as instruments of China’s public diplomacy. They analyze “three cases of a hybrid form of public diplomacy that combines state agencies and non-state actors in PPPs [public-private partnerships] involving multiple stakeholders, both domestic and transnational.”

Natalia Grincheva, Global Trends in Museum Diplomacy: Post Guggenheim Developments, (Routlege, 2019). Grincheva (University of Melbourne) make two central claims in this book. First, museums in the 21stcentury have evolved from publicly and privately funded repositories of cultural heritage to become actors in the economic sector of culture. Second, this transforms how we think about cultural diplomacy. Museums with global reach are now independent, non-government diplomatic actors engaged in diplomatic activities without support from national governments. She opens with an examination of the way states have partnered with museums to promote national cultures and support geopolitical interests. She then turns to the way the Guggenheim Foundation is changing this model with its strategies of museum franchising and global corporatization. Her reasoning is grounded in analysis of arguments academics and practitioners make on the merits and limitations of the Guggenheim model, examination of cultural diplomacy as “a contested academic field,” and deeply researched case studies of Russia’s Hermitage Museum and China’s K11 Art Foundation. Grincheva’s book is a more complete statement of ideas she advanced in The Hague Journal of Diplomacy’sspecial issue on non-state diplomacy annotated above. Scholars recently have done convincing work in developing conceptual frameworks for a polylateral diplomacy domain in which non-state actors function as independent diplomatic actors. Their standing as diplomacy practitioners turns not on sovereignty or association with governance actors, but on assessments of their contributions to diplomacy-based outcomes perceived as legitimate in the eyes of global publics. Grincheva’s work is a useful contribution to case studies and practitioner-oriented research needed to support these theoretical arguments.

Diana Ingenhoff and Sarah Marschlich, “Corporate Diplomacy and Political CSR: Similarities, Differences and Theoretical Implications,” Public Relations Review, 45 (2019), 348-371. Ingenhoff and Marschlich (University of Fribourg, Switzerland) review the literature on corporate diplomacy (CD) and political corporate social responsibility (PCSR) from the cross-disciplinary perspectives of journals in public relations, public diplomacy, general management, and business ethics. Their goals are first to examine definitions and theories in the CD and PCSR domains and then to identify differences and commonalities underlying the two concepts. Building on this research, they seek to redefine CD and PCSR and develop a theoretical framework for CD that integrates PCSR, international public relations, and public diplomacy. Strengths of their article rest on their extensive literature review and discussion of conceptual issues. Their proposed theoretical framework for corporate diplomacy, which attempts to integrate PCSR, public relations, and public diplomacy, raises many interesting and difficult issues that the authors and readers likely will agree warrant considerable further discussion and research. (Courtesy of Kathy Fitzpatrick)

Samantha Power, The Education of an Idealist: A Memoir, (Illustrated, 2019). In his review, New York Times columnist Tom Friedman states: “I can imagine a course for incoming diplomats at the State Department that would use Power’s book as a text, and the final exam question would be: ‘In 500 words or less, explain whether you identify with the younger Power or the older Power.’” Friedman’s thought experiment nicely frames Power’s reflections on her early career as a journalist, human rights activist, and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of A Problem from Hell: America in the Age of Genocide and her subsequent years as a foreign policy advisor, UN Ambassador, and idealism advocate on team Obama. The younger Power is an unambiguous champion of “responsibility to protect,” an unstinting critic of America’s inaction in the face of the Armenian massacre, the Holocaust, Rwanda, and Bosnia. The older Power is forced to deal with the in-house realities of White House decision-making on Iraq, Syria, Libya, Afghanistan, and Boko Haram. As both journalist and diplomat, her voice is consistently on the side of intervention, but her self-critical assessment avoids easy answers and fully embraces complexity. Along the way, her memoir covers her Irish family roots, years as a Harvard student and activist, enthusiasm for baseball, challenges of a professionally engaged mother, insights on diplomatic history, moral arguments in foreign affairs, and skills she deployed in the public and private dimensions of UN diplomacy. See also Dexter Filkins, “Damned If You Don’t: Samantha Power and the Moral Logic of Humanitarian Intervention,” The New Yorker, September 16, 2019.

“Public Diplomacy in the Trump Administration,” Panel Discussion at The Heritage Foundation, C-Span2 video streamed live on September 30 2019, (approximately 1 hour). The Heritage Foundation’s Public Diplomacy Fellow Helle Dale moderates a panel discussion with Michele Guida, Acting Under Secretary of Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs; Nicole Chulick, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Global Public Affairs; Matthew Lussenhop, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs; and Chris Dunnett, Deputy Coordinator, Global Engagement Center, Department of State. Panelists discuss recent organizational changes in the Department, including the creation of a new Bureau of Global Public Affairs, and related matters in US public diplomacy.

Susan Rice, Tough Love: My Story of the Things Worth Fighting For, (Simon & Schuster, 2019). Rice’s memoir adds to the growing abundance of evidence that US diplomacy’s public dimension is government-wide. Although there is much of interest about her family, ancestral roots, growing up in Washington DC, education at Stanford and Oxford, and political activism, more relevant for diplomacy enthusiasts are pages of insights from her years as NSC Director for International Organizations and Peacekeeping, Assistant Secretary of State for Africa, UN Ambassador, and President Obama’s National Security Advisor. Rice’s riveting story is about policies, personalities, rivalries, organizational cultures, diplomatic strategies, and time and again about shaping public argument and perceptions. A tiny sample: what to do about the term genocide and hate radio on Radio Mille Collines in Rwanda, Benghazi attack talking points, education for girls initiatives in Africa, communication strategies for summits and presidential trips, media and crisis management, and countless speeches, Congressional statements, dealing with leaks, press interviews, cable and Sunday talk shows – and much more.

Simon Schunz, Giles Scott-Smith, and Luk Van Langenove, “Broadening Soft Power in EU-US Relations,” European Foreign Affairs Review, Volume 24, Issue 2 (2019), 3-19. In this article, Schunz (College of Europe), Scott-Smith (Leiden University), and Van Langenove (Vrije University, Brussels) frame research questions for articles in this special issue of the Review that examines the role soft power “plays and should play as a ‘glue’ holding Transatlantica together.” Transatlantica is their term for a coherent regional political order with shared values created by the US and Europe that is being challenged from within, particularly by President Trump’s “America First” policies, and from increasing opposition by other powers to the post World War II order. The authors refine and broaden the concept of soft power focusing on how culture, science, and education have been linked as policy fields to the exercise of soft power. They pose research questions relating to the way actors interact in soft power domains, analysis of existing forms of interaction, and possible future areas of soft power-based interaction. They conclude with a discussion of academic, policy, and normative implications of their findings.

Simon Schunz and Riccardo Trobbiani, “Diversity Without Unitiy: The European Union’s Cultural Diplomacy Vis-à-vis the United States,” European Foreign Affairs Review, Volume 24, Issue 2 (2019), 43-62. Schunz (College of Europe) and Trobbiani (United Nations University) examine the complex domain of EU cultural diplomacy in the US and make the central claim that its “severe incoherencies” derive from a “legal framework protecting state sovereignty,” promotion of member states’ national interests, and a focus on what makes Europeans distinct rather than what they have in common. They call for a unified strategic approach to “communicating Europe” with priority attention to selected themes and policies while otherwise preserving diversity.

Giles Scott-Smith, “Transatlantic Cultural Relations, Soft Power, and the Role of US Cultural Diplomacy in Europe,” European Foreign Affairs Review, Volume 24, Issue 2 (2019), 21-41. Scott-Smith (Leiden University) in this contribution to the Review’s special issue (annotated above) draws on his extensive knowledge of American studies, cultural diplomacy, and transatlantic relations in this assessment of US cultural diplomacy in Europe during the Cold War and following 9/11. His article includes a discussion of conceptual issues in cultural diplomacy and soft power, institutional and operational characteristics of US Cold War cultural diplomacy, and ways in which US cultural diplomacy was “securitized” in the 21st century. He concludes an analysis framed largely as a 70-year history of state-based US cultural diplomacy with a brief observation that “state-led coordination of soft power assets is changing radically.” The rise of well-endowed philanthropies and other non-state actors pursuing “their own agendas of transatlantic linkage and integration demonstrates that state-led initiatives are declining in relative importance.” Further research and development of this argument would be welcome.

Efe Sevin, Emily Metzgar, and Craig Hayden, “The Scholarship of Public Diplomacy: Analysis of a Growing Field,” International Journal of Communication, 13(2019), 4814-4837. Sevin (Towson University), Metzgar (Indiana University), and Hayden (Marine Corps University), three of the most active and knowledgeable scholars in diplomacy and communication studies today, provide an excellent evidence-based survey of public diplomacy as a field of academic inquiry. Their article (1) addresses “the challenge of drawing institutional and conceptual boundaries for research;” (2) analyzes decades of English language peer-reviewed public diplomacy articles (N = 2,124); (3) highlights trends in scholarship, patterns of topics that co-occur, and ways topics vary among countries and regions; (4) identifies and ranks journals that publish articles on public diplomacy; (5) offers thoughts on conceptual boundaries in the field drawing on high frequency concepts and topics in the literature, and (6) makes recommendations for future work.

They acknowledge limitations in their data set, particularly the absence of rich insights available in think tank and government policy reports. Nevertheless, they reach interesting conclusions well worth ongoing discussion. Researchers should be more receptive to insights and literature beyond their own disciplines if public diplomacy is to deserve the label cross-disciplinary. Articles on public diplomacy have not consistently appeared in “higher tier” journals, which points to a lack of visibility and potential for future studies. The oft-lamented absence of a unifying theory of public diplomacy may be a strength rather than a constraint. The authors have made a valuable contribution to an area of study long challenged by definitional differences, unclear institutional and conceptual boundaries, uncertain connections with other disciplines, and a disconnect between what scholars and academic professional associations are doing and the relatively few courses and degree programs in academic institutions.

Dina Smeltz, et al. “Rejecting Retreat: Americans Support US Engagement in Global Affairs,” The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, September 6, 2019. In this latest survey of American public opinion, Dina Smeltz and her colleagues at the Chicago Council find that “large numbers of Americans continue to favor the foundational elements of traditional, post-World War II US foreign policy.” (1) “Today, seven in 10 Americans (69%) say it would be best for the future of the country to take an active part in world affairs.” (2) Solid majorities “say that preserving US military alliances with other countries (74%), maintaining US military superiority (69%), and stationing US troops in allied countries (51%) contribute to US safety.” (3) “More Americans than ever before in Chicago Council polling endorse the benefits of international trade for the US economy (87%) and for American companies (83%).” (4) “But the American public divides sharply along partisan lines when it comes to three threats to the United States: on immigration, climate change, and China.” Here “the gap between Democrats and Republicans is at record highs.”

Richard Stengel, The Information Wars: How We Lost the Global Battle Against Disinformation and What We Can Do About It, (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2019). Stengel, (NBC/MSNBC analyst and Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs in the Obama administration) has written what he calls “the story of the rise of a global information war that is a threat to democracy and to America.” He divides his story, told through his experiences at the Department of State, into three parts. (1) An outsider’s critique of the Department’s ways and culture. Lots of accurate and penetrating “ouch” observations. (2) Analysis confined largely to the “information wars” and “weaponized grievance” of Russia and ISIS; an assessment of how the “US tried – and failed – to combat the global rise of disinformation;” and an America “badly damaged” by Donald Trump. (3) Views on what should be done. He has little to say about how government should change, although his sympathies incline to maintaining an effective Global Engagement Center, and he only occasionally mentions international exchanges. Stengel’s reform agenda focuses on society’s role in dealing with false information. His mixture of remedies includes a new “digital bill of rights” and optimized “transparency, accountability, privacy, self-regulation, data protection, and information literacy.” Stengel writes as a former Time magazine editor. Paragraph after paragraph puts you in the room with the personalities of the moment and his version of events. Messaging and information wars dominate. It’s the story of a journalist who came to government as a self-described “information idealist” and left as an “information realist.” See also Richard Stengel, “We’re In the Middle of a Global Information War. Here’s What We Need to Do to Win,” Time, September 26, 2019.

US Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy, “Minutes and Transcript From the Quarterly Public Meeting on Public Diplomacy and the Global Public Affairs Bureau Within the Department of State,” September 4, 2019. The Commission’s meeting focused on the Department’s recent merger of its Bureau of Public Affairs and Office of International Information programs into a Bureau of Global Public Affairs. Participants included Commission Chair Sim Farar, Commissioners Bill Hybl and Anne Wedner, Executive Director Vivian Walker, Assistant Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs Michelle Giuda, and Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Global Public Affairs Bureau Nicole Chulick. Presentations and Commission and audience questions addressed the Department’s reasoning and vision for the reorganization and a variety of operational issues.

Recent Blogs and Other Items of Interest

Matt Armstrong, “The Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs: an Updated Incumbency Chart and Some Background,” August 26, 2019, Mountainrunner.us.

Martha Bayles, “Hollywood’s Great Leap Backward on Free Expression,” September 15, 2019, The Atlantic.

Peter Beinart, “Obama’s Idealists [Susan Rice, Samantha Power, and Ben Rhodes]: American Power in Theory and Practice,” November/December 2019, Foreign Affairs.

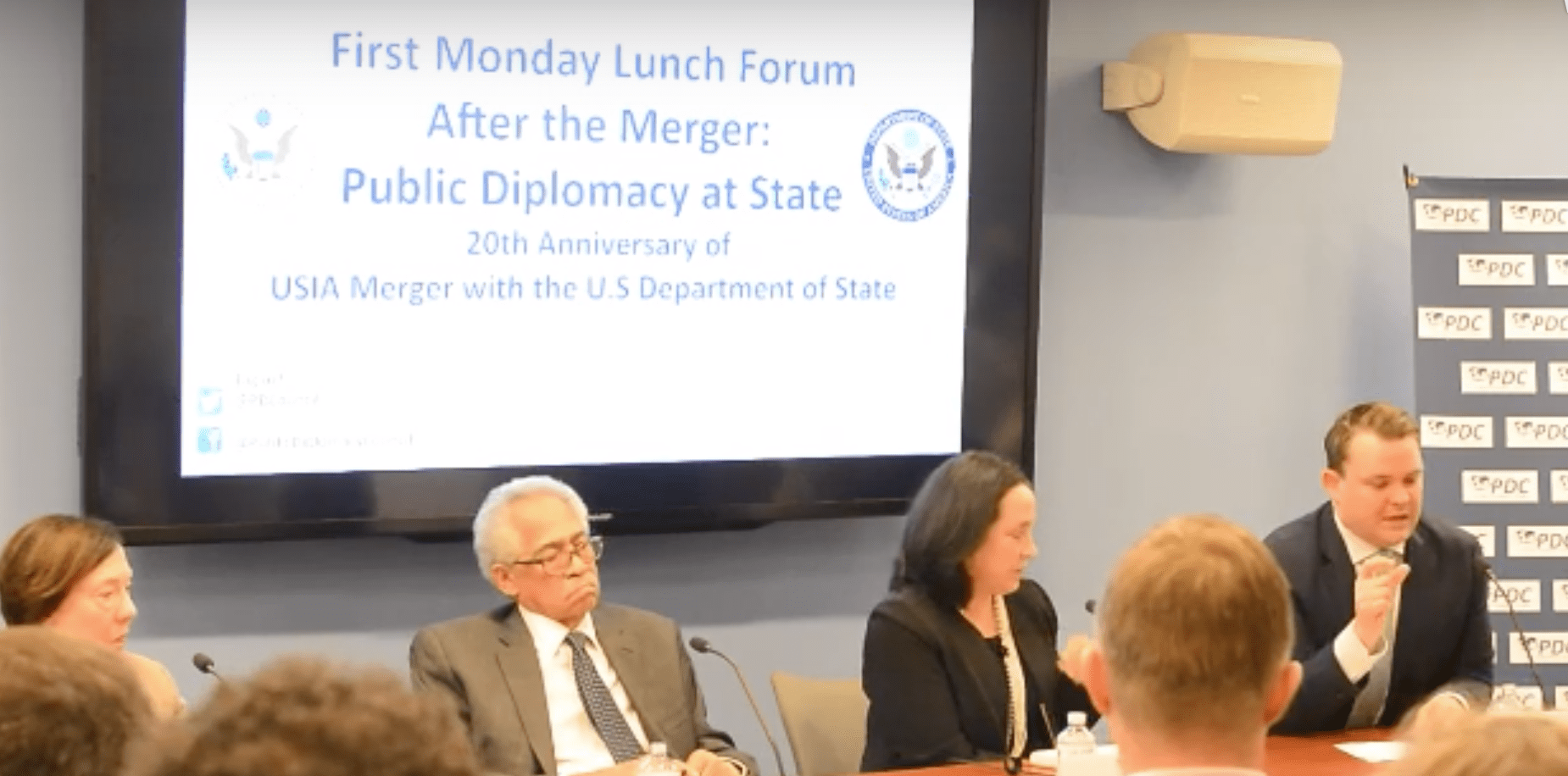

The First Monday Forum: “After the Merger: Public Diplomacy At State” with Ambassadors Cynthia Efird, Kenton Keith, Jean Manes, and USAGM’s Shawn Powers. A discussion of the merger of USIA and public diplomacy into the U.S. State Department in 1999. Produced by the Public Diplomacy Council, the Public Diplomacy Association of America, USC’s Center on Public Diplomacy and hosted in cooperation with George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs – October 7, 2019.

Corneliu Bjola, “Diplomacy in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” October 31, 2019, CPD Blog, USC Center for Public Diplomacy.

William J. Burns, “The Demolition of U.S. Diplomacy: Not Since Joe McCarthy Has the State Department Suffered Such a Devastating Blow,” October 14, 2019, Foreign Affairs.

Michael Carpenter and Spencer P. Boyer, “Americans and Russians Should be Friends – Even If Their Countries Aren’t,” October 14, 2019, Foreign Policy.

Nicholas J. Cull, “Expo Diplomacy 2020: Why the U.S. Needs to Go Back to the Future,” September 19, 2020, CPD Blog, USC Center for Public Diplomacy.

Christopher Datta, “Foreign Service Resignations: Why I Stayed,” September 2019, American Diplomacy.

Elizabeth Fitzsimmons, “A Love Letter to the State Department. Why I Stay. Yes Even Now,” September 18, 2019, The New York Times.

Andreas Fulda, “Chinese Propaganda Has No Place on Campus: Universities Can’t Handle Confucius Institutes Responsibly. The State Should Step In,” October 15, 2019, Foreign Policy.

Philip Gordon and Daniel Fried, “The Other Ukraine Scandal: Trump’s Threats To Our Ambassador Who Wouldn’t Bend,” September 27, 2019, The Washington Post.

Robbie Gramer and Amy Mackinnon, “Pompeo’s State Department Reels as Impeachment Inquiry Sinks Morale,” October 11, 2019, Foreign Policy.

Robbie Gramer, “Career Diplomats Fear Trump Retaliation Over Ukraine,” October 24, 2019, Foreign Policy.

Bruce Gregory, “Memories of Lou Olom (1917-2019),” September 29, 2019, Public Diplomacy Council; September 28, 2019, Public Diplomacy Association of America.

Anemona Hartocollis, “International Students Face Hurdles Under Trump Administration Policy,” August 28, 2019, The New York Times.

David Ignatius, “Why America Is Losing the Information War to Russia,” September 3, 2019, The Washington Post.

“Iraq Suspends US-funded Broadcaster Al Hurra Over Graft Investigation,” September 2, 2019, Reuters

Quinta Jurecic, “The Lawfare Podcast: Introducing the Arbiters of Truth,” October 31, 2019, Lawfare.

Joe B. Johnson, “After the Merger: Public Diplomacy 20 Years After USIA,” October 11, 2019; Public Diplomacy Council Blog; Panel discussion with Ambassadors Cynthia Efird, Kenton Keith, and Jean Manes and USAGM’s Shawn Powers, “First Monday” Forum, October 7, 2019, 90 minute Youtube video.

Ilan Manor, “Power in the 21st Century: The Banality of Soft Power,” October 21, 2019; “Power in the 21stCentury: A Reconceptualization of Soft Power,” October 28, 2019, CPD Blog, USC Center for Public Diplomacy.

Bethany Milton, “My Final Break With the Trump State Department,” August 26, 2019, The New York Times.

Ryan Moore, “Propaganda Maps to Strike Fear, Inform, and Mobilize – A Special Collection in the Geography and Map Division,” September 25, 2019, Library of Congress Blog.

Leila Nazarian, “Nonprofit Art Organizations as Credible Actors in Cultural Diplomacy,” September 5, 2019, CPD Blog, USC Center for Public Diplomacy.

Christina Nemr and Will Gangware, “The Complicated Truth of Countering Disinformation,” September 20, 2019, War on the Rocks.

Scott Pelley, “Brain Trauma Suffered By U.S. Diplomats Abroad Could Be Work of Hostile Foreign Government,” September 1, 2019, CBS 60 Minutes; Brit McCandless Farmer, “Is An Invisible Weapon Targeting U.S. Diplomats,” September 1, 2019, 60 Minutes Overtime.

Sudarsan Raghavan, “Egypt Expands Its Crackdown to Target Foreigners, Journalists and Even Children,” October 30, 2019, The Washington Post.

Erich J. Sommerfeldt and Alexander Buhmann, “The Status Quo of Evaluation in Public Diplomacy: Insights from the US State Department,” April 2019, Journal of Communication Management.

Bridget Sprott, “The Next Phase of PD: Instagram Diplomacy,” October 3, 2019, CPD Blog, USC Center for Public Diplomacy.

Louisa Thomas, “The N.B.A. and China and the Myths of Sports Diplomacy,” October 22, 2019, The New Yorker.

“USAGM Board of Governors Announces CEO For Interim Period,” September 25, 2019, US Agency for Global Media.

Layne Vandenberg, “Sports Diplomacy: The Case of the Two Koreas,” October 10, 2019, The Diplomat.

Menachem Wecker, “Why the Baroque Politeness of Diplomatic Notes is What the World Needs Now,” August 19, 2019, The Washington Post Magazine.

Li Yuan, “China’s Soft Power Failure: Condemning Hong Kong’s Protests,” August 20, 2019, The New York Times.

Gem From The Past

Kathy R. Fitzpatrick, The Future of Public Diplomacy: An Uncertain Fate, (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2010). It’s coming up on ten years since the publication of American University Professor Kathy Fitzpatrick’s book on US public diplomacy. Much has changed since then, but her scholarship continues to illuminate. She combines insights grounded in her study of public relations theory with extensive research in secondary sources on public diplomacy and a 15-page survey completed by 213 retired public diplomacy professionals and members of the USIA Alumni Association (recently renamed the Public Diplomacy Association of America). Her methods and observations are an excellent example of how diplomacy studies benefit from greater attention to what practitioners think and do and how practitioners gain from more explicit theorizing about their work. Examples appear throughout the book. A chapter on commonalities and differences between nation branding and public diplomacy remains an excellent, teachable summary of concepts and practices. Likewise her chapter on measuring success in public diplomacy evaluation. And her assessment of improvements needed in skill sets and recruitment practices. Most of the diplomats interviewed served during the Cold War and after – before the transformational changes in today’s political, media, and global issues context. Scholars might well consider interviewing a successor generation of recent retirees to analyze changes and continuities.